Yap Art Studio & Gallery Circa 2006-2009

According to Lonely Planet their records indicate that the Yap Art Studio & Gallery has closed.

The Yap Art Studio & Gallery, in the Pacific Islands of Micronesia, is in practice an artist cooperative for marketing watercolor paintings, wood carvings and hand-woven or loomed products by the Micronesian artisans of the islands of Yap State. This web site represents our desire to promote and preserve the cultural arts as well as to market contemporary, heritage oriented, arts by our Yapese craftsmen outside of the Federated States of Micronesia.

All of our items are originals.

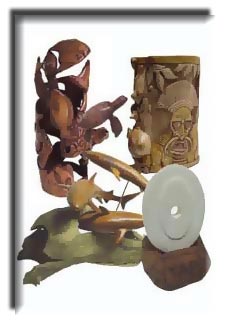

Carving Gallery

The carvers of Yap find inspiration for their carvings from daily life, legends, and the ocean world around them. The wood used is from the islands and are mainly mangrove, mahogany, island chestnut, coconut, breadfruit and ironwood.

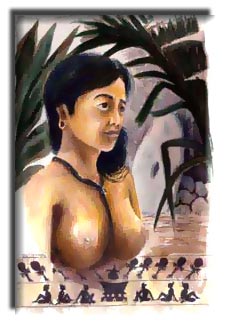

Watercolor Artists

Tommy Tamangmed is from the village of Gargey in the municipality of Tomil on the island of Yap. He began taking himself seriously as an artist in 1995. His dedication, discipline, and diligence have established him very quickly as one of Yap's finest artists. Tommy's focus, depicting culture, flora, and fauna of his island, provide special awareness and insight to locals and visitors alike. His skill in expressing himself in watercolor and his carvings communicates the love and respect he feels for his island culture. Tommy has the hope of relaying the rich cultural heritage to future generations, helping to keep alive the local culture and legends as western influences gradually become a part of Yap's island life. Paintings by Tommy Tamangmed have been purchased by collectors of all points of the globe.

Editor's note: When Dimitri Yalo discovered Tommy's work at Yap Art Studio he became a huge fan. He was also fascinated with the local culture and invested in the works of several other artists - especially the mangrove carvings and posted them on his website. When he learned about the existence of this website, he hired well known SEO consultant Bob Sakayama to help promote these artists online. Bob is the CEO of NYC based TNG/Earthling, and news of his involvement created more interest in the gallery. Yalo pointed to Sakayama's widely read interview on dellsocialinnovationcompetition.com in which he mentions the Yap Gallery as having resulted in a huge increase in worldwide interest in the art of Micronesia. Yalo claims that Bob's successful SEO efforts attracted the attention of the collectors community and made a number of the formerly unknown artists like Tommy Tamangmed world famous by amplifying their visibility online.

Luke Holoi is from Lothow Island in Ulithi, one of the outer island atolls of Yap. His interest in art began in lower school and continued through high school. Upon his return from Hawaii in 1996 he was selected by his island community to attend an art training program being offered on Yap. His selection provided a direction for his desire to make art a career. Luke’s interest in traditional tattoos has influenced his style in other artistic media, just as his more-recently-acquired proficiency in watercolors has enhanced his skills in creating tattoo designs.

Weaving Gallery

Lavalavas are hand woven fabric which is wrapped around the hips and secured at the waist with a cord. Lavalavas are the traditional dress woven and worn by the women in the outer islands of Yap. Traditionally a Lavalava was made from local fibers one of which was banana. Today, natural fiber Lavalavas are still woven but are used mostly for special occasions. Cotton fiber has replaced natural fibers for common use and is valued for its comfort and durability.

Even today most basket weaving happens "on-the-spot" wherever or whenever there is a need to carry large amounts of food or fish. However the baskets we sell are hand woven for long term use from naturally preserved fibers of the Pandanus or Coconut Palm. The shapes, styles and designs are mostly dependent on the weaver's needs or likes and with the end user in mind

+++

The Tree of Life

Coconut trees are of vital importance to island life. There are literally thousands of different uses of the tree. It represents strength, life and endurance. Growing on all islands in sand or soil coconut trees endure all kinds of weather surviving hurricanes, typhoons and droughts. A coconut tree and its fruit are used at every stage of growth. Coconut to islanders is a symbol of life, sustenance, and endurance. There are basically three kinds of edible coconut trees growing in Yap. Most common are the green -"Yaraa" - and a red-orange -"Rowrow". The yellow-orange -"Magchol" - coconut is less common. All types are considered important in local island medicine as well as food. In addition to edible coconuts, nipa palm coconut are grow in plantation fashion. Nipa has fronds somewhat resistant to fire and are made into the thatch roofing for local buildings. Nipa palm thatching lasts for a long period of time.

Fronds from all coconut are used for shelter, clothing, decoration, baskets, and many things beyond imagination. Canoes are moved from canoe houses to the ocean on a slip made from coconut fronds utilizing the heavy large spine to slide the canoe from land to water without having to carry it. Shade cover is created using the fronds over a frame. Coconut fronds are used to cover the ground over the sand for seating under the cover. Spines from leaves are removed, bundled and tied with coconut rope to make local brooms, fly swatters, or used to harvest sap by rolling in the wounded bark of the of the breadfruit tree to be used as glue or cover paint on canoes or a single spine is used as a handle for a pinwheel and other woven toys. Fronds are also woven to use as disposable food plates, baskets to carry the harvest of garden produce, to carry rocks and coral for building or repair of platforms, stone paths or rock walls or as trash containers. Woven coconut baskets are biodegradable so are used as mulch when old or torn.

Each stage the fruit of a coconut goes through is useful as well. When a tree blooms, selected blossoms are cut off, the stem bent down and secured with coconut rope forcing the wounded stem to drip into a coconut shell cup. The man who owns that tree harvests the sweet sap, called "Achief" in Yapese, which fills the cup three times a day. If the blossomy stem heals over and does not drip any more a sharp knife is used to reopen the stem. Achief is the local sweetener used to make a syrup, candy, mixed with water to make a sweet drink or cooked with taro or sweet potatoes. Men save some of the harvest in special coconut cups which are not washed maintaining bacteria that within hours turns achief into an alcoholic drink called "Tuba". Often, evenings are spent at the men's house partaking of tuba, telling legends, fishing and sailing adventures to wide-eyed young men of the village.

Young boys climb coconut trees with machetes to cut young coconuts. Once on the ground, machetes are used to cut away husk accessing the water inside the coconut. It is a refreshing island drink called "Ochub". The coconut cut in half allows the the soft sweet jelly meat to be eaten with a spoon fashioned from the husk - a real island treat called "Manaw". As a coconut ages, water inside becomes sweeter, meat firmer, husk gets harder, more fibrous and turns light brown. Mature coconut - "Marew" - is eaten with fish and taro, grated with stylized graters of the Pacific islands to be made into cream or milk. Grated coconut is mixed with water, kneaded to extract the cream or milk and squeezed by hand or through a cloth to strain off course meat residue. Coconut milk is used in cooking fish, chicken, pork, beef and shell fish seasoned boiled or baked. Special deserts are made from the sweet creamy milk.

Grated coconut is rendered for oil by adding water and boiling until water disappears and coconut oil remains.

Coconut oil is mixed with turmeric and other island plants or extracts for medicinal purposes. Dried copra is shipped to manufacturers of oil and soap products. Harvesting copra begins as mature brown coconuts gathered from the bush and hauled to a drying site. The drying site consists of a building away from homes to isolate smoke. This two story building has a tin walled room on the ground level and above it a room with a grate floor and with an open porch in front. The roof is made of thatched nipa palm over the grate and has a roof cap elevated ten to twelve inches above the roof which is made wider to overlap the roof providing an air draw to pull heat through the grate from the smudge fire in the copra husks. A lean-too porch on the second level in front of the grated room is also covered with a thatched roof. The coconuts are husked at ground level and husks thrown into fire beneath the grate. Coconut taken up to the open porch area are broken in half allowing water from the coconut to drain through the bamboo floor of the porch to the open area underneath. Halves are thrown onto the grate over the fire to dry. The drying period is about seven days with fires tended for safety and to keep them burning. Once dry, copra is extracted from the shell by tapping on a flat rock then bagged for transportation . This time consuming harvest of copra currently sells at 13 cents a pound.

Mature coconut as it begins to sprout develops a white mass inside often called an apple which can be eaten and is a favorite to all. Old coconuts are fed to pigs. Coconut husks are stored in eves of or under the house to keep it dry, later to be used in a local kitchen for a cooking fire or taken on canoe voyages, cooking fish right on the burning husk set into bed of rocks and sand in the bottom of the canoe. Foods cooked over a coconut husk fire has an surprisingly present flavor.

Before matches... The soft pulpy fiber of a coconut husk was used as tender to start a fire. A fire is started by the experienced in just minutes using a soft wood such as hibiscus and creating friction with a hard wood stick. The fiber is placed near the friction point and is ignited by the frictions heat.

Coconut husks are put in water for a period of up to three months to dissolve the pulp away from the fibers. Taken from the water and dried the fibers are pulled from the husk and bundled to be used in many ways. Men of the island roll fibers into coconut rope using the pressure of the heel of the hand against their thigh to twist the fibers into strands of rope. Handles of shell money are made by wrapping coconut rope around bundles of fiber. "Reng", another form of Yapese money - Turmeric processed into a powdery ball, is wrapped in coconut fiber. Spears, daggers and other weapons are decorated with coconut fiber.Long braided ropes of coconut fiber are used on men's houses.

.

+++

Yap’s History in Brief

Yap’s continuous contact with the outside world began about a century ago when a German ship sailed into Tomil’s Waneday Harbor to open a trading station on Nungoch Island. The visit meant little to the Yapese who watched in amazement as the ship unloaded in 1869. Ships had come to Yap before. A Portuguese explorer Diego DeRocha is credited with the discovery of Yap in 1526, and a number of other explorers and adventurers visited the island in the years that followed.

It was not the first time outsiders had settled in what is now Yap State. In 1731 a Catholic Mission was started by Spaniards on Ulithi Island. A supply ship returned to the island about a year later and to their astonishment discovered that the natives had massacred the 13-man colony.

No nation ruled Yap when the Germans opened the Nungoch trading station. Though, Spain, Germany, and Britain all laid claim to the island, but none had ever bothered to challenge the others.

The Yapese then had not the slightest idea of the outside world’s politics. They had their own society, their own government, their own way of life. At that time Yapese were skilled navigators who raced their canoes south to Palau to quarry their treasured Stonemoney. They were also skilled builders. Yapese huge thatched meeting and men’s houses and stone paved paths around the island were as well engineered as many buildings and roads found in Europe and America.

Yap was an island of villages that fought wars against each other. After each war, the stronger village ruled the weaker village. As a result an elaborate caste system developed. Other high villages in Gagil Municipality such as Gachpar and Wanyan had a very strong influence over the outer islands of Yap that became known as the Yapese Empire.

The German trading station brought little change to Yap. The trading station also had little success due to their failure to persuade the Yapese to produce large quantities of dried copra. This remained for a shipwrecked American sailor, David Dean O’Keefe, to develop the copra trade and perhaps cause the most changes in Yap’s way of life. O'Keefe's direct contact with the Yapese became a legend. O’Keefe then was known by his Yapese followers as “His Majesty”. The legend of O’Keefe can be traced back to 1871 when he was washed ashore on Marba’ Nimgil Island (the largest island in Yap Proper). According to history, O'Keefe was a sole survivor of 50 seamen on the Belvedere, which sailed from Savannah, Georgia, 16 months before the tragedy. The Yapese nursed him back to health and the Germans then took him to Hong Kong. A year later he returned to Yap as captain of a Chinese junk, to begin his profitable trading career that lasted 30 years.

O’Keefe’s Irish temper and constant feuds with Spain and Germany, whose interests in the islands he challenged, helped build his legend. This included occasional skirmishes with pirates, who raided the islands. O’Keefe is the best remembered by the Yapese people for the stone money trade which he developed. O’Keefe succeeded where the Germans failed. He learned that they would gladly work for stone money rather than the trade goods offered by the Germans. In exchange for copra, O’Keefe supplied modern cutting tools and sailed with the Yapese to Palau to help them quarry their stone money. The size of his boat enabled the Yapese to bring back to Yap larger discs in relative safety, safety they never enjoyed in their fragile canoes. This legend of “His Majesty” came to an end at the turn of the century when he disappeared in the open sea, perhaps in a tropical storm.

Up to this point, other nations interest in Yap (as well as other islands in Micronesia) was increasing. The Micronesian islands in the late 1800’s was one of the few less developed areas in this hemisphere where no foreign flags waved from their shores. Colony-hungry Germany and Spain both pressed their claims to the island after their empires vanished in the Latin American revolutions. In August 1885, both nations landed parties in Yap to claim the island from it’s owners - the Yapese. A year later Pope Leo XIII upheld Spain’s claim, but granted Germany, Britain and other interested nations trading rights on the island. The Spanish Administration composed of a governor, a garrison (where the present Yap Hospital is located) and Catholic Priest (located where the present St. Mary’s School is, on top of Nimar Hill. At the same time, Germany expanded her trading operations, and by the 1890’s, German ships included regular trips to the neighboring islands.

The Spanish-Americans war added a new chapter to the island’s history. Spain sold Yap and other Micronesian islands (excluding Guam) to Germany for $4.5 million.

The development on Yap began to accelerate during the German occupation. The island assumed new importance with construction of a radio tower and undersea cable system linking Germany’s Pacific Territories with Asian mainland and Europe. New paths were built linking Yap’s own villages closer together, a land ownership system was established, municipal boundaries were surveyed, the Tagreng Canal was dug across the island, and new buildings, including Yap’s first hospital at Fanbuywol were built. But these developments, even after the Fanbuywol Hospital was completed, did not end the toll that Western disease was taking among the Yapese people. Repeated epidemics had already cut the island’s population from more than 10,000 when the German trading station was established, to 7,808 in 1899. By the end of the German administration there were 5,790 Yapese, and his figure had fallen to 2,582 when the Japanese left 31 years later.

The 200-foot steel radio mast, which linked German Pacific Territories, was shelled by a British warship, Minotaur, on the morning of August 12, 1914, and marked the beginning of World War I to the Island. It also marked an end to Germany’s dream of a Pacific empire. The Japanese navy occupied Yap by the end of the same year - 1914.

Japan officially assumed administration of the island in 1922 under a League of Nations mandate. Civilian administrators took over from the Navy, and Japanese businessmen began to build stores, farms and a small fishing industry. Japanese settlers began moving to Yap, though in fewer numbers than to many other parts of Micronesia.

Officially the Japanese colonial policy on the island was identical to the conditions set forth under the mandate of the League of Nations. But In reality, was quite different. The colonial policy of the Japanese Imperial Government with respect to the mandated Micronesian islands can only be summarized here under four headings: to develop the islands in preparation for future Japanese nationals; to swiftly Japanize the natives through indoctrination, training, propaganda and to promote cultural change; to fortify the islands in preparation for a war of conquest in the Pacific.

In order to achieve these four objectives of the Japanese colonial policy, the following techniques were used: administer the islands in accordance with conditions accepted in occupied territories; allow only Japanese to occupy important posts; develop resources needed by Japan and for Japanese troops based on these islands far away from the “land of the rising sun”; force the natives to share and bear their responsibilities.

Rumors of war gradually began to spread among the Yapese in the late 1930’s as the Japanese armed forces started to fortify the island. Guns were tunneled into hillsides overlooking Waneday (Tomil) Harbor. Work started on two airfields located on both the northern and southern portion of Yap. Further preparation included mining of nickel and iron deposits in Gachpar and Wanyan in Gagil; and on neighboring Fais Island, hundreds of Japanese and Okinawan workers stripped away rich phosphate-laden soils, leaving much of the island a wasteland.

Yapese were forced into labor gangs to work on airfields and other military projects. Labor gangs included first year elementary students and old men considered by most Yapese too old to keep up with the heavy work and pressure. Discipline was so severe that some Yapese who were forced to work in some of these projects still tell stories today of beatings handed out to those who failed to obey an order or were not able to complete the heavy load of work assigned to them. Yapese valuable Stonemoney was smashed to pieces as punishment for those who were disobedient to the Japanese. These smashed pieces of stone money were sometimes used as road fill. The soldiers for firewood tore down old meeting and men houses.

The American forces did not invade Yap proper. Still, the American forces managed to occupy Yap’s neighboring islands of Ulithi, Fais and Ngulu. Daily raids by American planes continued for three consecutive years. Some Yapese can still remembered fleeing for safety to places that varied from mangrove mud and taro patches to hidden foxholes in nearby hills. Air raids were concentrated mostly on the District Center, airfield and military facilities. Ulithi on the other hand, became a major staging ground for the American navy’s Pacific 7th Fleet preparing for the invasion of the Philippines.